Smoking Cessation Reduces Postoperative Complications a Systematic Review and Metaanalysis Pdf

Abstract

Purpose

The literature was reviewed to determine the risks or benefits of short-term (less than four weeks) smoking cessation on postoperative complications and to derive the minimum elapsing of preoperative forbearance from smoking required to reduce such complications in developed surgical patients.

Source

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, and other relevant databases for cohort studies and randomized controlled trials that reported postoperative complications (i.e., respiratory, cardiovascular, wound-healing) and mortality in patients who quit smoking within six months of surgery. Using a random furnishings model, meta-analyses were conducted to compare the relative risks of complications in ex-smokers with varying intervals of smoking cessation vs the risks in current smokers.

Master findings

We included 25 studies. Compared with electric current smokers, the risk of respiratory complications was similar in smokers who quit less than ii or two to iv weeks before surgery (chance ratio [RR] 1.20; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.96 to 1.50 vs RR ane.14; CI 0.xc to 1.45, respectively). Smokers who quit more than four and more than eight weeks before surgery had lower risks of respiratory complications than current smokers (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.61 to 0.96 and RR 0.53; 95% CI 0.37 to 0.76, respectively). For wound-healing complications, the risk was less in smokers who quit more than three to iv weeks before surgery than in current smokers (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.84). Few studies reported cardiovascular complications and at that place were few deaths.

Decision

At least four weeks of abstinence from smoking reduces respiratory complications, and forbearance of at least iii to 4 weeks reduces wound-healing complications. Brusque-term (less than iv weeks) smoking cessation does not appear to increase or reduce the take chances of postoperative respiratory complications.

Résumé

Objectif

La littérature disponible a été passée en revue cascade déterminer les risques ou avantages d'united nations arrêt du tabagisme à court terme (moins de quatre semaines) sur les complications postopératoires et pour en déduire la durée minimum d'abstinence tabagique préopératoire qui permet de diminuer la survenue de ces complications chez des adultes subissant une chirurgie.

Source

Notre étude a porté sur les bases de données MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, et les autres bases de données pertinentes à la recherche d'études de cohortes ou d'études randomisées et contrôlées ayant décrit les complications postopératoires (c'est-à-dire respiratoires, cardiovasculaires, retard de cicatrisation) et la mortalité chez des patients ayant cessé de fumer dans les vi mois ayant précédé l'intervention chirurgicale. Des méta-analyses ont été effectuées en utilisant un modèle à effets aléatoires pour comparer les risques relatifs de complications chez les anciens fumeurs, avec des délais variables d'arrêt du tabagisme, aux risques chez des fumeurs actifs.

Constatations principales

Nous avons inclus 25 études. Comparés aux fumeurs actifs, les risques de complications respiratoires ont été comparables chez les fumeurs ayant cessé de fumer moins de deux semaines, ou entre deux et quatre semaines avant une intervention chirurgicale (rapport de risque [RR]: i,xx; intervalle de confiance [IC] à 95 %: 0,96-one,fifty, contre, respectivement, RR: 1,14; IC à 95 %: 0,90-1,45). Les fumeurs ayant cessé de fumer plus de quatre semaines et plus de huit semaines avant fifty'intervention chirurgicale avaient des risques de complications respiratoires moins élevés que les fumeurs actifs (RR: 0,77; IC à 95 %: 0,61-0,96 et RR: 0,53; IC à 95 %: 0,37-0,76, respectivement). Concernant les complications liées à la cicatrisation, le risque a été plus faible chez les fumeurs ayant cessé plus de trois à quatre semaines avant 50'intervention que chez les fumeurs actifs (RR: 0,69; IC à 95%: 0,56-0,84). Peu d'études ont décrit des complications cardiovasculaires et il northward'y a eu que peu de décès.

Decision

Un minimum de quatre semaines d'abstinence du tabagisme diminue le risque de complications respiratoires et un minimum de trois à quatre semaines réduit le risque de complications liées à la cicatrisation. L'arrêt à court terme (moins de quatre semaines) du tabagisme ne semble pas augmenter ou réduire le risque de complications respiratoires postopératoires.

Smoking is associated with increased postoperative morbidity and mortality.one-iii This is a major concern equally up to xx% of surgical patients are smokers.4,v A recent big observational study of not-cardiac surgical patients reported that smoking is associated with a 38% increase in the risk of perioperative expiry and a thirty-109% increase in the risk of serious postoperative complications, depending on the blazon of complication.3 However, this report did non examine whether curt-term abstinence from smoking before surgery reduces the risk of postoperative complications.

A relatively long period of abstinence from smoking before surgery reduces postoperative complications.6,seven Ii systematic reviews showed that preoperative smoking cessation programs increased short-term (upwardly to six months) abstinence.8,ix Consequently, both the American Society of Anesthesiologists10 and the Canadian Anesthesiologists' Society11 recommend promoting smoking cessation earlier surgery. However, surgery is frequently scheduled within a few weeks of diagnosis of certain conditions, thus precluding longer periods of preoperative abstinence. Likewise, anesthesiologists typically see patients within i to four weeks of planned surgery. Anesthesiologists may be reluctant to advocate smoking abeyance before long earlier surgery considering the benefits of a brusque flow of abstinence (less than four weeks) are uncertain, and in that location could possibly exist increased risks of postoperative respiratory12 or cardiovascular complications, or mortality.13 Interestingly, a paradoxical effect of lower mortality and improved consequence was observed in smokers compared with non-smokers after astute myocardial infarction, middle failure, and stroke.14-16 These data suggest that information technology may be inappropriate to stop smoking shortly before surgery.

A recent meta-assay constitute that smoking cessation less than viii weeks earlier surgery did not increment or decrease the charge per unit of overall or respiratory complications.17 However, the authors pooled studies with varying elapsing of smoking cessation (2 to eight weeks before surgery) and did not examine wound-healing complications. Therefore, the issue of abeyance of smoking shortly earlier surgery is still unclear.

It is important to make up one's mind the benefits or risks of brusk-term abstinence from smoking before surgery in order to guide anesthesiologists and other clinicians when providing preoperative advice to smokers. The objectives of this systematic review are to determine the benefits or risks of short-term (less than four weeks) abstinence from smoking compared with continued smoking on postoperative complications (respiratory, cardiovascular, wound-healing) and mortality and to determine the minimum duration of preoperative smoking cessation to reduce postoperative complications.

Methods

Search strategy

In collaboration with a research librarian, we searched Medline (Jan 1950 - April 2010 and May 2010 - January 2011), EMBASE (January 1980 - Jan 2011), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (January 2005 - January 2011), and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (January 2011). Searches were conducted using two different components: ane) Smoking/Smoking cessation and related terms component 2) Preoperative/Surgery/Anesthesia and related terms component. Both text-word and index-word terms were used; the text word terms in our search strategies included smoke*, nicotine?, cigar*, preop*, preoperat*, perioperat*, preanesthe*, presurg*, surger*, surgical*, operat*, resect*, operati*, performance?, operative*, anesthe*, anaesthe*, perisurg*, preadmit*, and preadmission*. The following exploded index-give-and-take terms were used: 'tobacco use abeyance', 'smoking cessation', 'smoking', 'tobacco', 'tobacco employ disorder', 'nicotine', 'preoperative care', 'preoperative period', 'perioperative intendance', 'perioperative nursing', 'surgical procedures, operative', 'general surgery', 'anesthesiology' and 'anesthesia'. Manufactures were limited to human studies and to the English language linguistic communication (Appendix). The bibliographies of retrieved articles and relevant reviews were searched manually for farther studies.

Study selection

Ii reviewers (J.W., D.Fifty.) independently screened titles and abstracts to identify studies reporting postoperative complications (respiratory, cardiovascular, wound-healing) or decease in relation to timing of preoperative smoking cessation within six months before surgery. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or by consulting the senior author (F.C.). All randomized controlled trials (RCT) and cohort studies were included.

Studies were excluded if the menstruum of smoking cessation was more than than vi months before surgery or not reported. Nosotros included RCTs that offered interventions if the complications were reported co-ordinate to the bodily smoking behaviour (i.e., continued to fume or abstained) regardless of the intervention that the patient was randomized to receive. Nosotros contacted the corresponding authors if complications were not reported co-ordinate to actual smoking status. Strategies were used to avoid indistinguishable publications.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (J.West., D.L.) independently extracted report characteristics and rated written report quality. The following information was extracted from each study: continent, number of report participants, description of intervention, study design, surgical procedure, duration of preoperative smoking cessation, and postoperative complications (equally reported in the primary studies) for ex-smokers, current smokers, and non-smokers. Respiratory complications included: bronchospasm needing handling, atelectasis requiring bronchoscopy and/or assisted ventilation, pulmonary infection, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, empyema, pulmonary embolus, adult respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory failure or arrest, re-intubation and ventilation, tracheostomy, and loftier inspired oxygen required for 24 hour. Cardiovascular complications included: life-threatening arrhythmias, severe hemodynamic disturbances, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and cerebral vascular accident. Wound-healing complications included: impaired wound healing requiring intervention (east.g., debridement or re-suturing), wound dehiscence, flap or fat necrosis, hernia, vessel thrombosis, wound hematoma, seroma, mediastinitis, wound infection with positive microbial culture or requiring antibiotic therapy, wound cellulitis and swelling. We as well extracted information most study quality, including number of dropouts, comparability of groups, adjustment for confounders, blinding, follow-upwardly catamenia, biochemical validation of smoking cessation, and funding source. Nosotros categorized non-smokers as those who never smoked; ex-smokers were those who stopped smoking any time earlier surgery, and current smokers were those who continued to smoke up to the day of surgery.

Quality cess

We did non assess the quality of the RCTs, as the objective of this review was not to determine the effectiveness of various interventions for reducing complications but rather to determine the effect of brusk-term smoking cessation on postoperative complications and the minimum duration of smoking cessation to reduce postoperative complications. We conformed to the Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) grouping guidelines.18 The quality of the studies was considered high if the blueprint, deport, and reporting of the studies were unlikely to be susceptible to bias. Loftier-quality studies fulfilled the following criteria: validation of self-reported smoking condition with biochemical methods, comparability of patients, adjustment for potential confounders for postoperative complications, acceptable length of follow-up, blinding of the result assessor, and reporting of the source of funding.

Information synthesis and assay

The primary outcome was the respiratory complications amid ex-smokers with less than two weeks and ii to four weeks of abstinence compared with electric current smokers. Secondary outcomes included postoperative complications (respiratory, cardiovascular, wound-healing) and mortality amid ex-smokers and smokers, smokers and non-smokers, ex-smokers and not-smokers.

Meta-analysis of the relative risks of complications (respiratory, cardiovascular, wound-healing) and mortality was performed in ex-smokers and smokers and ex-smokers and not-smokers when at least 2 studies comparing similar intervals were available. Nosotros also directly compared the relative risks of complications in dissimilar periods of preoperative smoking cessation with the risks in smokers and non-smokers. For the meta-analyses, nosotros planned to categorize ex-smokers into different preoperative smoking cessation periods, i.east., less than two weeks, ii to four weeks, more than than iv weeks, or more than eight weeks based on the cessation menstruum reported in the original studies. Due to the clinical differences between the studies (e.g., patient population, study pattern, etc.), a random-furnishings model was used in all meta-analyses. The Mantel-Haenszel test was used to calculate the hazard ratio (RR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) for each meta-analysis. The Iii statistic was used to measure out inconsistency amongst the written report results. nineteen A value > 50% may be considered moderate heterogeneity. Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.one (The Nordic Cochrane Middle, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011, Copenhagen) was used for all meta-analyses. Sensitivity analyses were performed for type of surgery (east.g., cardiac vs non-cardiac) and quality of study.

Results

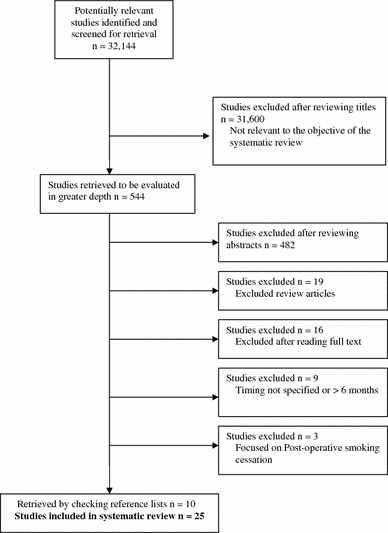

The search strategy yielded 32,144 citations. We identified 25 studies that fulfilled our inclusion criteria, for a full of 21,381 patients (Fig. 1). There were seven prospective accomplice studies,12,20-25 16 retrospective cohort studies,26-41 and two RCTs (Table 1).42,43 Both RCTs offered nicotine replacement therapy.42,43 There were 14 studies from North America,12,21,23,26,30-35,37,39-41 vi from Europe,22,27,28,38,42,43 4 from Asia,twenty,25,29,36 and one from Commonwealth of australia.24

Menses chart of the literature search and study selection

In that location were more than male than female smokers, and smokers were younger than non-smokers or ex-smokers in many of the studies. The type of surgery, definition of complications, elapsing of smoking cessation, and the definition of "non-smokers", "ex-smokers", and "current smokers" reported in the individual studies varied betwixt studies.

There were few studies that fulfilled most of the criteria for loftier quality (Table 1). Four studies used biochemical methods, including exhaled carbon monoxide and urinary cotinine concentrations, to validate the smoking condition of the patients.12,24,42 Four studies had comparable groups amongst smokers, ex-smokers, and non-smokers.43 Six of the observational studies adjusted for potential confounders (Table 1). The follow-upward periods were non specified in 13 studies (Table 1).12,20,22,27-thirty,33-38,40 The outcome assessor for postoperative complications was blinded to the smoking status of the patients in only v of the studies.12,29,36,42,43 All five studies reporting the source of funding received public funding,21,24,36,42,43 and the nicotine replacement products were provided by the manufacturers (Table ane).42,43

Respiratory complications

Fifteen studies involving 19,323 patients reported respiratory complications (Table ii, available equally electronic supplemental material [ESM]).12,20,21,23-32,40,42 There were four dissimilar fourth dimension points commonly reported by the studies for respiratory complications, i.e., less than 2 weeks, ii to iv weeks, more than 4 weeks, and more than eight weeks of smoking cessation before surgery. Xiv studies involving 17,160 patients were included in the meta-analyses.12,twenty,21,23-26,28-32,40,42 Eight of these studies involving three,331 patients were prospective.12,20,21,23-25,42,43 As there was only one report examining the effect of less than or more than 12 weeks cessation, nosotros could not perform a meta-assay of this time bespeak.27

Summary of meta-analyses of respiratory complications

(The individual meta-analyses are available as ESM, Figs 6-17).

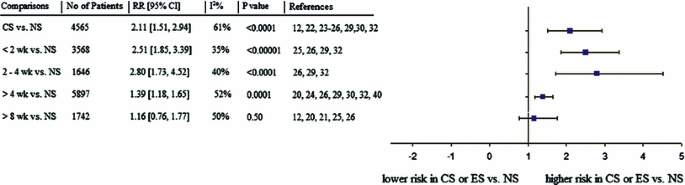

The relative risk (RR) of postoperative respiratory complications was higher in those who continued smoking at the time of surgery compared with non-smokers (RR 2.11; 95% CI i.51 to 2.94; Iii = 61%; P < 0.0001). When the catamenia of abstinence from smoking was more than than eight weeks, the risk was similar in ex-smokers and in not-smokers (RR 1.16; 95% CI 0.76 to one.77; I2 = 50%; P = 0.fifty), merely a shorter catamenia of forbearance failed to reduce the risk to values as low as those in non-smokers (Fig. two). The blazon of surgery largely explained the heterogeneity, and grouping similar types of surgery together, i.eastward., cardiac vs non-cardiac surgery, reduced heterogeneity.

Summary of the meta-analyses of postoperative respiratory complications in current smokers or ex-smokers compared with non-smokers. The squares indicate the overall relative risk and the horizontal lines indicate the 95% confidence interval for each time interval. CS = current smoker; NS = non-smoker; ES = ex-smokers

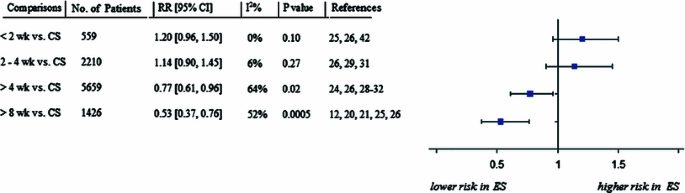

Compared with current smokers, the risk of respiratory complications was non higher in ex-smokers who abstained less than two weeks or two to iv weeks before surgery (Fig. three). On the other hand, the risks of respiratory complications in those who quit more than four weeks before surgery were significantly lower compared with current smokers (Fig. three). The RR was 0.77 (95% CI 0.61 to 0.96; I2 = 64%; P = 0.02) with more than than iv weeks of smoking cessation, and the RR was further reduced to 0.53 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.76; Iii = 52%; P = 0.0005) in those who quit more than viii weeks before surgery. The blazon of surgery, i.e., cardiac vs non-cardiac surgery, explained part of the heterogeneity at more than eight weeks but not at more than iv weeks. The number of loftier-quality studies with like smoking abeyance intervals was insufficient to perform sensitivity analyses.

Summary of the meta-analyses of postoperative respiratory complications in ex-smokers compared with current smokers. The squares indicate the overall relative risk and the horizontal lines indicate the 95% confidence interval for each time interval. CS = current smoker; NS = non-smoker

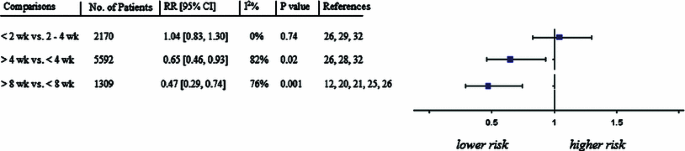

Direct comparisons of different intervals of smoking cessation and respiratory complications showed that in that location was no difference between patients who stopped smoking less than ii weeks vs ii to four weeks earlier surgery (Fig. 4). Notably, the risk of respiratory complications was lower in those who stopped smoking more than four weeks vs less than four weeks before surgery. Similarly, the RR was less in ex-smokers who quit more than eight weeks vs less than eight weeks earlier surgery (Fig. iv). The type of surgery, i.e., cardiac vs non-cardiac surgery, largely explained the heterogeneity at four weeks but not at eight weeks.

Summary of the meta-analyses of postoperative respiratory complications with direct comparisons of ex-smokers based on time of smoking cessation before surgery. The squares indicate the overall relative risk and the horizontal lines indicate the 95% confidence interval for each time interval

Cardiovascular complications

Cardiovascular complications were evaluated in only 5 studies involving i,818 patients.20,31,40,42,43 Ane of the RCTs did not report cardiovascular complications according to actual forbearance or continued smoking, and the authors did not respond to our asking for these data.43 There were no differences in risks for cardiovascular complications amongst electric current smokers, ex-smokers (one to viii weeks forbearance), and non-smokers (Table three; available as ESM). Withal, a meta-analysis on this result was not performed every bit there were few cardiovascular complications reported in the studies, and the sample sizes were limited.

Wound-healing complications and studies for performing a meta-analysis

In that location were 15 studies involving 9,536 patients that reported wound-healing complications (Table four, bachelor as ESM).22,24,27,28,33-43

There was only one time point (i.e., less than or more 3 to four weeks before surgery) with an acceptable number of studies for meta-analysis. Thirteen studies involving 7,265 patients were included in the meta-analysis.22,24,28,33-42 There was twice the take a chance of wound-healing complications in those who continued smoking at the time of surgery vs not-smokers (RR ii.08; 95% CI 1.sixty to ii.71; I2 = 8%; P < 0.00001) (Fig. 18, available as ESM).

The risk remained college in ex-smokers who quit smoking within iii to four weeks before surgery vs non-smokers (RR 1.64; 95% CI 1.40 to 1.92; Iii = 0%; P < 0.00001) (Fig. nineteen, available every bit ESM). However, risks of wound-healing complications in patients who abstained from smoking beyond three to iv weeks before surgery were similar to those in patients who had never smoked (RR i.44; 95% CI 0.97 to 2.15; I2 = 76%; P = 0.07) (Fig. twenty, available as ESM). The blazon of surgery did not explain the heterogeneity.

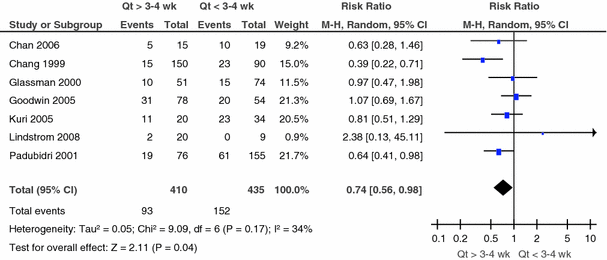

Ex-smokers who quit less than three to four weeks before surgery had similar risks for wound-healing complications as current smokers (RR = 1.22; 95% CI 0.56 to 2.67; I2 = 86%; P = 0.61) (Fig. 21, available equally ESM). The type of surgery did not explain heterogeneity, only the number of studies was limited at this time interval. The risks of wound-healing complications in ex-smokers who stopped smoking more than than three to four weeks earlier surgery were significantly lower than in electric current smokers (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.84; I2 = 0%; P = 0.0003) (Fig. 22, available as ESM). In add-on, direct comparisons showed the risk was significantly lower in ex-smokers who stopped smoking more than than 3 to iv weeks before surgery vs those who stopped less than 3 to four weeks before surgery (RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.98; Iii = 34%; P = 0.04) (Fig. 5). Therefore, more than three to 4 weeks of preoperative forbearance is necessary to reduce risks of wound-healing complications.

Ex-smokers who quit more than iii to four weeks earlier surgery had lower relative risks of postoperative wound-healing complications than those who quit less than 3 to iv weeks before surgery. The squares indicate the overall relative adventure and the horizontal lines signal the 95% conviction interval for each time interval. The diamond represents the pooled estimate. Qt = quit time; CI = confidence interval; Thou-H = Mantel Haenszel; wk = weeks

Bloodshed

X of the studies reported mortality rates.12,xx,21,23,27,28,thirty,32,42,43 One large retrospective study in pulmonary resections for lung cancer reported higher mortality in current and ex-smokers compared with not-smokers (i.5% vs 0.3%, respectively; P < 0.05).32 The other nine studies did non report differences in mortality amongst smokers who quit at unlike intervals before surgery and current and non-smokers.12,twenty,21,23,27,28,30,42,43 However, there were few deaths reported in the included studies, and the individual studies were not large enough to detect differences in mortality.

Discussion

This review supports the notion that there is a time-related decrease in the take a chance of respiratory complications, i.e. the relative risk decreases as the elapsing of preoperative smoking cessation increases. Well-nigh chiefly, cessation of smoking more than iv weeks earlier surgery reduced the risk of respiratory complications past 23%. Those who stopped smoking more than than eight weeks before surgery had greater benefits, and the risk of respiratory complications was reduced past 47%. Indeed, the risk of respiratory complications in those who stopped smoking more than eight weeks before surgery was comparable with non-smokers. In all probability, patients should terminate smoking at least 4 weeks, and preferably 8 weeks, before surgery to reduce postoperative respiratory complications. However, there was no testify that brusk-term abstinence from smoking (less than four weeks) before surgery increases or reduces postoperative respiratory complications compared with continued smoking, but only a few studies examined this interval. At that place was no departure in mortality between smokers and ex-smokers, but at that place were few deaths reported in the included studies.

Our meta-analysis shows that smokers who abstained more than three to iv weeks before surgery had fewer wound-healing complications than current smokers. Likewise, smokers who quit more than iii to four weeks earlier surgery had fewer wound-healing complications than those who quit less than three to iv weeks before surgery. Our results are consistent with a well-conducted report in wound healing following excisional dial biopsy that reported a reduction in the incidence of wound infections with iv weeks of abstinence from smoking.44 However, this report was not included in our review as it did non involve a surgical process.

We did not find evidence to support that curt-term abstinence from tobacco may lead to acute withdrawal, increased sympathetic activity, and increased cardiovascular complications. However, a limited number of studies reported cardiovascular complications. Therefore, we could not determine the take chances or benefits of smoking abeyance for prevention of cardiovascular complications.

The findings of our systematic review and meta-analysis are consequent with previous reviews and extend their findings.half-dozen,7,17 Our review included more studies than a previous review which was limited to a comparing of smokers vs ex-smokers who quit less than eight weeks earlier surgery.17 We also examined wound-healing complications, and we did non puddle the results of studies with unlike periods of cessation. In contrast, by comparing different intervals of short-term cessation with continued smoking and including studies that directly compared different intervals of abeyance (e.g., less than two weeks vs ii to four weeks) on postoperative complications, nosotros were able to determine the minimum duration of preoperative smoking cessation necessary to reduce postoperative respiratory and wound-healing complications. Our findings besides confirm that smokers have higher risks for postoperative respiratory and wound-healing complications than non-smokers.3

The results of our review should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations of the included studies. Few studies had loftier methodological quality, and most of the included studies were retrospective observational studies. However, information technology would be difficult to perform a prospective trial with randomization of patients to different periods of forbearance before surgery. Our conclusions are based on the best evidence that is currently available. The majority of the studies relied on self-reporting of smoking status, which may take led to the status beingness inaccurately reported. Many of the studies did not adjust for confounding factors between groups. The study designs and definition of postoperative complications varied among the studies. As well, the smoking abeyance intervals in some studies were not clearly defined, and intervals overlapped with more than one time interval. To overcome this trouble, we grouped together similar intervals of the reported smoking cessation periods and compared them collectively. In add-on, many of the studies did not report clinically meaning outcome measures, including recovery room and hospital length of stay. Some other limitation of this review is our exclusion of articles not published in English.

The heterogeneity was moderate or high for a few of the meta-analyses. The type of surgery could explain some of the heterogeneity; nevertheless, smoking increases complications beyond all non-cardiac surgical procedures3 and including different types of surgery increases generalizability of our findings. The number of high-quality studies with like smoking cessation intervals was insufficient to perform the relevant sensitivity analysis. Other factors that explain the heterogeneity may include the wide range of time intervals vs clearly defined intervals reported in individual studies. Sensitivity analyses of other potential factors explaining heterogeneity, such every bit affliction severity, patient morbidity, etc., were non possible due to limited data reported in the private studies. Withal, heterogeneity exists in the amount of overall event, not in the management of the issue, i.e., although the RRs were unlike, all were on the same side of the Woods plot. Nonetheless, nosotros used the random effects method, which is more suitable when heterogeneity exists.45

In conclusion, at least four weeks of preoperative smoking cessation is necessary to reduce respiratory complications, and at least three to four weeks of forbearance is needed to reduce wound-healing complications. Based on the bachelor studies examining short-term (less than iv weeks) abstinence from smoking, short-term forbearance does not increase or reduce postoperative respiratory complications. Withal, given the known long-term benefits of smoking abeyance, including an comeback in long-term health, and the "teachable moment" a pre-access visit provides, our findings should not deter anesthesiologists and other perioperative clinicians from counselling surgical patients to stop smoking regardless of the time of visit. Time to come studies should examine the ideal time frame for smoking cessation prior to surgery, consider adjusting for confounders, and target more clinically meaning outcomes, such as hospital length of stay.

References

-

Warner DO. Perioperative abstinence from cigarettes: physiologic and clinical consequences. Anesthesiology 2006; 104: 356-67.

-

Warner Do. Tobacco dependence in surgical patients. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2007; 20: 279-83.

-

Turan A, Mascha EJ, Roberman D, et al. Smoking and perioperative outcomes. Anesthesiology 2011; 114: 837-46.

-

Agostini P, Cieslik H, Rathinam S, et al. Postoperative pulmonary complications following thoracic surgery: are there any modifiable risk factors? Thorax 2010; 65: 815-8.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Cigarette smoking amongst adults and trends in smoking cessation - United states, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009; 58: 1227-32.

-

Theadom A, Cropley M. Furnishings of preoperative smoking abeyance on the incidence and risk of intraoperative and postoperative complications in adult smokers: a systematic review. Tob Control 2006; fifteen: 352-eight.

-

Mills E, Eyawo O, Lockhart I, Kelly S, Wu P, Ebbert JO. Smoking abeyance reduces postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med 2011; 124: 144-54e8.

-

Thomsen T, Tonnsen H, Moller AM. Effect of preoperative smoking cessation interventions on postoperative complications and smoking cessation. Br J Surg 2009; 96: 451-61.

-

Zaki A, Abrishami A, Wong J, Chung F. Interventions in the preoperative dispensary for long term smoking cessation: a quantitative systematic review. Can J Anesth 2008; 55: 11-21.

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists. Statement on Smoking Abeyance (2008). Bachelor from URL: http://www.asahq.org/For-Healthcare-Professionals/Standards-Guidelines-and-Statements.aspx (accessed January 2011).

-

Canadian Anesthesiologists Society. Terminate Smoking for Safer Surgery. Bachelor from URL: http://world wide web.cas.ca/English/Stop-Smoking (accessed January 2011).

-

Warner MA, Offord KP, Warner ME, Lennon RL, Conover A, Jansson-Schumacher U. Function of preoperative smoking cessation and other factors in postoperative pulmonary complications: a blinded prospective written report of coronary avenue bypass patients. Mayo Clin Proc 1989; 64: 609-16.

-

Ruiz-Bailen One thousand, de Hoyos EA, Reina-Toral A, et al. Paradoxical effect of smoking in the Spanish population with astute myocardial infarction and unstable angina. Breast 2004; 125: 831-40.

-

Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. A smoker'due south paradox in patients hospitalized for heart failure: findings from OPTIMIZE-HF. Eur Heart J 2008; 29: 1983-91.

-

Ovbiagele B, Saver JL. The smoking-thrombolysis paradox and acute ischemic stroke. Neurology 2005; 65: 293-5.

-

Ferreira R. The paradox of tobacco: smokers accept a better post-infarct prognosis (Portuguese). Rev Port Cardiol 1998; 17: 855-half dozen.

-

Myers G, Hajek P, Hinds C, McRobbie H. Stopping smoking soon before surgery and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curvation Int Med 2011; 171: 983-9.

-

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-assay of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting: Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) grouping. JAMA 2000; 283: 2008-12.

-

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557-60.

-

Azarasa M, Azarfarin R, Changizi A, Alizadehasl A. Substance use among Iranian cardiac surgery patients and its effects on short-term consequence. Anesth Analg 2009; 109: 1553-9.

-

Barrera R, Shi W, Amar D, et al. Smoking and timing of cessation: touch on on pulmonary complications after thoracotomy. Chest 2005; 127: 1977-83.

-

Araco A, Gravante G, Sorge R, Araco F, Delohu D, Cervelli Five. Wound infections in aesthetic abdominoplasties: the office of smoking. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 121: 305e-10e.

-

Bluman LG, Mosca 50, Newman Due north, Simon DG. Preoperative smoking habits and postoperative pulmonary complications. Chest 1998; 113: 883-9.

-

Myles PS, Iacono GA, Hunt JO, et al. Risks of respiratory complications and wound infection in patients undergoing ambulatory surgery: smokers versus nonsmokers. Anesthesiology 2002; 97: 842-7.

-

Yamashita S, Yamaguchi H, Sakaguchi G, et al. Upshot of smoking on intraoperative sputum and postoperative pulmonary complexity in minor surgical patients. Respir Med 2004; 98: 760-6.

-

Warner MA, Divertie MB, Tinker JH. Preoperative abeyance of smoking and pulmonary complications in coronary artery bypass patients. Anesthesiology 1984; 60: 380-iii.

-

Ngaage DL, Martins E, Orkell E. The impact of the duration of mechanical ventilation on the respiratory event in smokers undergoing cardiac surgery. Cardiovasc Surg 2002; 10: 345-50.

-

Al-Sarraf North, Thalib L, Hughes A, Tolan M, Young V, McGovern E. Outcome of smoking on short-term outcome of patients undergoing coronary artery featherbed surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 86: 517-23.

-

Nakagawa Thousand, Tanaka H, Tsukuma H, Kishi Y. Human relationship between the duration of the preoperative smoke-gratuitous catamenia and the incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications later on pulmonary surgery. Breast 2001; 120: 705-ten.

-

Vaporciyan AA, Merriman KW, Ece F, et al. Incidence of major pulmonary morbidity afterward pneumonectomy: clan with timing of smoking cessation. Ann Thorac Surg 2001; 73: 420-6.

-

Groth SS, Whitson BA, Kuskowski MA, Holmstrom AM, Rubins JB, Kelly RF. Impact of preoperative smoking status on postoperative complication rates and pulmonary part exam results ane-yr post-obit pulmonary resection for non-modest jail cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2009; 64: 352-7.

-

Mason DP, Subramanian S, Nowicki ER, et al. Bear on of smoking abeyance before resection of lung cancer: a Society of Thoracic Surgeons Full general Thoracic Surgery Database Report. Ann Thor Surg 2009; 88: 362-71.

-

Chang DW, Reece GP, Wang B, et al. Event of smoking on complications in patients undergoing free TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000; 105: 2374-80.

-

Padubidri AN, Yetman R, Browne Eastward, et al. Complications of postmastectomy chest reconstructions in smokers, ex-smokers, and nonsmokers. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001; 107: 342-9.

-

Goodwin SJ, McCarthy CM, Pusic AL, et al. Complications in smokers after postmastectomy tissue expander/implant chest reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 2005; 55: xvi-20.

-

Kuri M, Nakagawa One thousand, Tanaka H, Hasuo S, Kishi Y. Determination of the elapsing of preoperative smoking cessation to improve wound healing after head and neck surgery. Anesthesiology 2005; 102: 892-6.

-

Spear SL, Ducic I, Cuoco F, Hannan C. The effect of smoking on flap and donor-site complications in pedicled TRAM breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005; 116: 1873-fourscore.

-

Chan LKW, Withey Southward, Butler PE. Smoking and wound healing problems in reduction mammaplasty: is the introduction of urine nicotine testing justified? Ann Plast Surg 2006; 56: 111-5.

-

Glassman SD, Anagnost SC, Parker A, Burke D, Johnson JR, Dimar JR. The effect of cigarette smoking and smoking cessation on spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000; 25: 2608-15.

-

Moore South, Mills BB, Moore RD, Miklos JR, Mattox TF. Perisurgical smoking cessation and reduction of postoperative complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 192: 1718-21.

-

Taber DJ, Ashcraft Due east, Cattanach LA, et al. No deviation between smokers, former smokers, or nonsmokers in the operative outcomes of laparoscopic donor nephrectomies. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2009; 19: 153-half dozen.

-

Lindstrom D, Azodi Os, Wladis A, et al. Effects of a perioperative smoking cessation intervention on postoperative complications: a randomized trial. Ann Surg 2008; 248: 739-45.

-

Moller AM, Villebro N, Pedersen T, Tonnesen H. Effect of preoperative smoking intervention on postoperative complications: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2002; 359: 114-seven.

-

Sorensen LT, Karlsmark T. Gottrup F Abstinence from smoking reduces incisional wound infection: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2003; 238: 1-five.

-

Higgins JP, Light-green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.0.two [updated September 2009]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009. Available from URL: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org (accessed January 2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely give thanks Marina Englesakis BA (Hons) MLIS, Information Specialist, Surgical Divisions, Neuroscience & Medical Pedagogy, Health Sciences Library, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada for her assistance with the literature search.

Funding

This work was funded by the Section of Anesthesia, Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network, and Academy of Toronto. No external funding. Dr. Wong is a recipient of a Academy of Toronto Merit Research Award.

Annunciation of interests

Dr. Chung has received a research grant from Pfizer Inc. The other authors have cypher to declare.

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author contributions

Jean Wong was involved in data abstraction, interpretation of information, drafting and revising, and concluding approving of the article. David Paul Lam was involved in data abstraction and drafting of the article. Amir Abrishami was involved in drafting and revising the article, data analysis, and interpretation of the data. Matthew Chan revised and approved the final version of the article. Frances Chung was involved in the conception and design, revising, and final approving of the article.

Electronic supplementary material

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this article

Wong, J., Lam, D.P., Abrishami, A. et al. Brusque-term preoperative smoking cessation and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anesth/J Tin Anesth 59, 268–279 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-011-9652-x

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1007/s12630-011-9652-x

Keywords

- Postoperative Complication

- Smoking Abeyance

- Current Smoker

- Risk Ratio

- Cardiovascular Complication

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12630-011-9652-x

0 Response to "Smoking Cessation Reduces Postoperative Complications a Systematic Review and Metaanalysis Pdf"

Post a Comment